Investigation Xoth: Smartphone location tracking

ExpressVPN’s Digital Security Lab conducted exclusive research on location trackers embedded in 450 social, messaging, and cultural apps to measure the extent to which they intrude on location privacy for individuals around the world.

Introduction

Location data is commonly harvested from consumer smartphones. A person’s location information has broad applications in the advertising and analytics industry, with the potential for enriching user profiles and providing insights into user behavior via intimate details about a user’s movements. Additionally, correlations can be made between users and their distance from Internet-of-Things (IoT) beacon devices. Such methods utilize Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) technology to provide proximity information that is valuable for a wide range of industries including retail and entertainment. This union of brick-and-mortar sensors with network technology has been amplified by Covid-19, and major players such as Google and Apple have boosted BLE-based products in response to the pandemic.

Increasingly, the data collected by location and proximity sensors ends up in the hands of law enforcement, intelligence agencies, and military organizations. These government entities and their private contractors are amassing huge troves of data about the movements of entire populations. This threatens not only the privacy of ordinary people around the globe but also their autonomy—knowledge of a person’s location can be abused to trample their human rights, including free expression and association, as well as cause chilling effects.

Today, the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab is releasing exclusive research about a growing threat to location privacy: A diverse collection of hundreds of mobile apps all linked by major intrusions on consumer privacy. We call this effort “Investigation Xoth,” after a fictional intelligence group in Cory Doctorow’s novel Attack Surface. The trackers found in these 450 apps are notable not only for their global reach but also a continual presence at the heart of privacy scandals.

We prepared this report with the aid of Esther Onfroy of the Defensive Lab Agency and with the app scanner provided by Exodus Privacy. The results of our investigation are described below, providing new and original insight into expansive and pervasive smartphone surveillance.

Key findings

We identified location tracker SDKs in 450 apps that have been downloaded at least 1.7 billion times. Though U.S. government scrutiny continues to grow, 67% (305) of these apps remained as of January 2021.

Location trackers appear in 42 messaging apps with at least 187 million downloads, including apps masquerading as popular services such as Telegram, Facebook Messenger, and WeChat.

X-Mode, the subject of a ban by Apple and Google, is prevalent in many more apps than previously reported, appearing in 44% (199) of the apps we analyzed that have been downloaded at least 1 billion times. Despite the ban, only 10% of these apps have been removed from Google Play.

Surveillance of Muslim audiences via apps is much larger than previously reported, with X-Mode and related location tracker SDKs identified in ten religious and cultural apps with at least 67 million downloads.

Dating and social apps are a notable target of location tracker SDKs, making up 64 of the 450 apps we analyzed with at least 52 million downloads.

Quadrant, a location tracker with over 60 million daily active users, is present in two apps that have been central in recent privacy scandals.

References to OneAudience, which was sued by Facebook for privacy violations, are present in 37% (167) of the apps we analyzed.

For a full lists of apps and more tracker information, visit our repository of detailed findings.

What are tracker SDKs?

A Software Development Kit (SDK) is a package of code that provides functionality for app developers. This functionality may include features such as maps, communication with Bluetooth devices, or even graphics and emojis. Sometimes, however, these SDKs also include code utilized for advertising and surveillance.

SDKs are bundled in a smartphone app’s code before it is published in an app store, and therefore are difficult to detect by Google, Apple, or others. Even if a developer announces that it is including a specific SDK in its app, smartphone users are not made aware of its presence when they install an app on Android or iOS.

For privacy and security investigations, it can be crucial to determine what SDKs are present in an app. SDKs execute code and communicate over the internet in ways that may compromise user information. In some cases, SDKs are designed specifically to collect and aggregate data about the behavior, location, or identities of smartphone users. In other cases, such surveillance is a valuable byproduct of the SDK’s core functionality—an app that provides navigation while you are driving, for example, may also be tracking your movements throughout the day and sending that data back to the app’s developers and third parties.

In these cases, we call the SDKs “trackers” or “tracker SDKs.” We follow the lead of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Fight for the Future, and other digital rights organizations and use the term broadly: “Trackers” encompasses traditional advertisement surveillance, behavioral, and location monitoring. Legitimate uses may include user feedback mechanisms, telemetry, and crash reporters.

App developers have decided to include tracker SDKs in apps for a variety of reasons, and we do not categorize all usage of trackers as malicious or condemn the app authors. Additionally, given the complexity and pace of software development, some developers may not be aware that trackers are in their app or may not know the full implications of bundling such code before publishing.

Searching for SDKs

Researchers have made efforts to automate, or partially automate, the process of detecting SDKs in apps. In our investigation, we used a combination of automated tools and manual analysis. In all cases, we determine whether there are “signatures” or identifying information for a tracker in an app’s code, gathering other interesting information such as network endpoints that the app may communicate with. A rough outline of the process is:

Download and unpack the app installer

Disassemble machine language into human-readable source code

Search source code for tracker signatures and other identifiers

Correlate findings with web databases, public information, and app stores

Our research in this area is constrained to Google Play and Android apps. We took this approach in the interest of concision and because static analysis on Apple iOS apps is limited by logistical barriers and uncertain legal status. We note that Android is the world’s most popular mobile operating system, with nearly 73% market share.

The smartphone surveillance ecosystem

Smartphones have spawned entire industries based upon discovery and analysis of consumers. Within the massive world of smartphone tracking, there are companies that specialize in a particular form of surveillance (e.g., Bluetooth tracking) as well as sprawling data brokers who collect and analyze troves of information.

Due to the sheer size and complexity of the smartphone ecosystem, and the data-sharing relationships between the entities that inhabit it, limiting the scope of research can be difficult. Despite the complexity of these connections, a comparative approach is vital to understanding tracker SDKs and the common threads between them.

In the past two years, news has piled up about tracker SDKs inside apps that are linked to government, military, and law enforcement organizations. As the public learns more about these actors, a bigger picture is beginning to emerge. At the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab, we want to help put the puzzle together and empower consumers to better understand how their use of certain apps may have privacy and security implications.

We started our investigation with apps that have well-known privacy issues and worked outward, discovering tracker SDKs in a collection of 450 apps.

The X-Mode connection

Investigation Xoth began by analyzing Muslim Pro, an application downloaded at least 50 million times from Google Play. Muslim Pro was the subject of an exposé by Vice Motherboard in November 2020, where it was revealed that it “obtains location data directly from apps, then sells that data to contractors, and by extension, the military.” X-Mode had been flagged in previous stories as a location tracker, where threat intelligence firms were said to be “buying location data harvested from ordinary apps installed on peoples' phones around the world.”

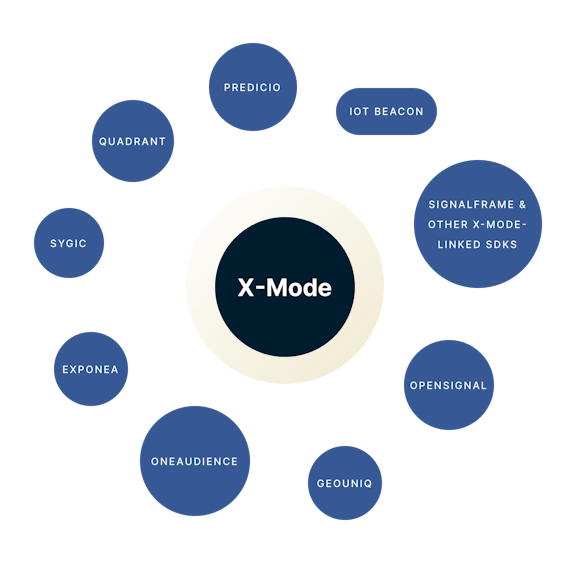

X-Mode makes no secret of its prowess in gathering and analyzing location data, “receiving the majority of its data directly from mobile app publishers through XDK, its proprietary location-based SDK.”

X-Mode’s approach is multi-faceted, “ensuring that companies have access to a higher standard of location data by tapping into a variety of technologies that most companies do not use.” This approach has, however, been the subject of U.S. congressional scrutiny and has resulted in a ban by Apple and Google.

Despite this ban, our investigation found that X-Mode maintains a strong presence on Google Play. We identified 199 apps with X-Mode tracker SDKs in them, collectively downloaded at least 1 billion times. 90% of these apps continue to be listed in Google Play after the ban.

Along with these findings, Digital Security Lab has identified novel insights that reveal the scope of X-Mode’s penetration.

In addition to the ”io.xmode” location SDK, we identified “io.mysdk” as an additional SDK that exists in the “X-Mode XDK Visualizer” app. Identification of this new signature allowed us to find many more X-Mode apps than had previously been known.

X-Mode “io.mysdk” code lists five providers for communication with location-snooping beacons. These are Placed (a subsidiary of Foursquare), Sense360, Wireless Registry (aka SignalFrame), BeaconsInSpace (aka Fysical), and OneAudience.

By monitoring network endpoints that are persistent across X-Mode apps, such as “api.myendpoint.io” and “api.smartechmetrics.com,” we observed beacon configuration information crossing the internet.

At least seven apps targeting Muslim audiences contain X-Mode, in addition to the presence of X-Mode previously discovered in Muslim Pro.

Beacon buddies

Each of the names listed in X-Mode’s beacon-communicating code is notable. Wireless Registry, for example, is the former name of SignalFrame and the handle used for its patented “observer SDK.” The recipient of a U.S. Air Force grant, SignalFrame has reportedly “developed the capability to tap software embedded on as many as five million cellphones to determine the real-world location and identity of more than half a billion peripheral devices.”

OneAudience is well known as the subject of a ban and lawsuit by Facebook for privacy violations. In February 2020, Facebook and Twitter claimed that “OneAudience had been harvesting private data, such as people’s names, genders, emails, usernames, and potentially people’s last tweets” in a scandal reminiscent of Cambridge Analytica. This ultimately led to a shutdown of the SDK.

Sense360, BeaconsInSpace (aka Fysical), and Placed (a subsidiary of Foursquare) are all prominent players in location surveillance. As with SignalFrame and OneAudience, their relationship with X-Mode is unclear. We provide the following observations.

Placed, Sense360, Wireless Registry, BeaconsInSpace, and OneAudience are listed as “enabled” by default in X-Mode SDK configuration files.

SDKs from these companies and associated network endpoints are in notable apps. We identified the BeaconsInSpace SDK in Muslim Pro, SignalFrame SDK and OneAudience SDK in Muslim Mingle, and Sense360 SDK and Placed SDK in a variety of apps containing X-Mode.

GeoUniq (aka Cloud4Wi), a trusted partner of X-Mode, is present in a variety of sports and entertainment apps, downloaded at least 6.2 million times.

A 2016 BeaconsInSpace presentation lists popular Android and iOS apps. The status of SDK code in these apps is unknown. Sygic, provider of a navigation app “trusted by more than 200 million drivers,” is listed alongside popular apps such as Navmii, TripWolf, and Pokémon Go Map Radar.

Local snooping, global impact

Our findings underscore the international reach of location surveillance that originates with consumer smartphones and retail beacon devices. Though Muslim audiences are a conspicuous target, the apps we analyzed aim at a wide range of populations worldwide. This is perhaps most apparent in dating and social apps that list specific demographics or countries in their names.

We discovered crossover between these apps and yet more SDKs embroiled in privacy scandals such as Predicio, present in Muslim prayer app Salaat First, and Sygic, provider of Slovakia’s contact-tracing app.

Predicio and Sygic were also the subjects of a December 2020 investigation by Norwegian outlet NRK. That report followed data through a maze of location surveillance vendors, disclosing that third parties “could use this information for purposes such as federal law enforcement and national security.”

One app, Fu*** Weather, is central to that story. While analyzing the app, we discovered a new tracker signature: That of Quadrant “Data Acquisition” SDK, which boasts a presence in apps with hundreds of millions of monthly active users worldwide. In December 2020, Quadrant tracked approximately 41 million active users per day and 136 million active users in the U.S. alone.

We found Quadrant in a handful of apps, including one app that brings our investigation full circle. Quadrant is present in the source code of Muslim Pro, perhaps the most prominent carrier of X-Mode.

In addition, we provide the following insights.

Dating and social apps are a notable component of the global presence, making up 64 of the 450 apps we analyzed with at least 52 million downloads. These dozens of apps target a range of sexual orientations as well as a large assortment of national, ethnic, and racial groups.

Predicio is present in twelve messenger apps, including apps masquerading as Telegram and WeChat. X-Mode is present in apps such as Messenger Go and Messenger Pro that mimic the branding of Facebook Messenger, with at least 60 million downloads.

Infinario (aka Exponea) provides analytics for the Sygic SDK, present in five out of the seven apps containing Sygic code.

Conclusion

At the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab, we have demonstrated the value of holistic and comprehensive analysis of a group of apps. This approach leads to novel discoveries and allows us to better understand patterns in digital surveillance.

Through Investigation Xoth, we identified evidence of the ubiquity of location tracking SDKs in a wide range of consumer apps. The overlap and correlations between some of these SDKs echo findings by journalists and academics, suggesting relationships between various location trackers.

Though trackers may be nominally banned from app stores, further investigation reveals these measures are not being consistently enforced and do not take into account the relationships between SDKs. Serious auditing of apps before publishing is the only way to keep trackers out of app stores and, even then, detection requires care and dedication.

For more information on what consumers should do to protect themselves, please visit our blog.